GENRE: Experimental

LABEL: AD 93

REVIEWED: 23rd September, 2025

RATING: 9.1/10

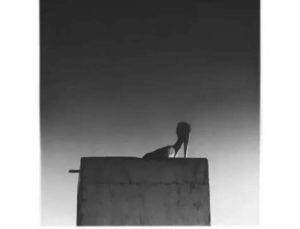

Joanne Robertson’s Blurrr, released in September 2025 on AD 93, is a strikingly intimate record that feels as much like a whispered confession as it does a finished album. Known both as a painter and as a musician, Robertson has always blurred the line between the visual and the sonic, and here she delivers her most resonant solo work to date. Much of the music was written in the quiet hours between painting and parenting, and that sense of solitude and compressed time saturates the record. It sounds like a private diary accidentally left open, filled with sketches that somehow cohere into something hauntingly beautiful.

The album begins with “Ghost,” a hushed entrance that sets the tone for everything to follow. Robertson’s guitar playing is delicate and spare, her voice drifting in and out of clarity, almost as if she is half-remembering her own lyrics. This elusiveness is central to the album’s character; words blur into sound, and melodies dissolve into atmosphere. The cello of Oliver Coates enters on several songs, not dominating but deepening the mood, expanding the space without breaking its fragile intimacy. On tracks like “Gown” and “Doubt,” the cello folds into Robertson’s guitar and voice until the line between instrument and echo disappears, creating moments of quiet transcendence.

Listening to Blurrr is like walking through a foggy evening: everything is visible but indistinct, and the ambiguity becomes its own kind of beauty. Songs stretch out in unhurried arcs, often improvised yet still shaped by a subtle internal rhythm. The guitar figures are open-ended, strummed in ways that let silence fill the gaps, while Robertson’s vocals hover on the edge of articulation. There is a palpable sense of solitude, but not isolation—it feels more like someone inviting you into their most unguarded moments, asking you to lean in and listen closely.

What makes the record so powerful is its restraint. Nothing feels ornamental, nothing unnecessary. Even in its imperfections—the crack of a voice, the roughness of a chord—the album holds its ground, making honesty the point rather than polish. For some listeners, this minimalism may verge on frustrating. The lyrics can be difficult to make out, and stretches of the record drift without clear resolution. But for those attuned to its wavelength, Blurrr offers a profound experience: music that doesn’t tell you what to feel, but instead creates a space in which emotion arises naturally.

The closing track, “Last Hay,” leaves the listener in a state of quiet reflection, closing the album as gently as it began. Taken as a whole, Blurrr feels less like a collection of songs and more like a sustained mood, a series of emotional fragments that piece together into something whole. It is the sound of solitude turned outward, of private thoughts finding form.

In the end, Robertson’s Blurrr stands as her most affecting work yet. It is modest in its means but ambitious in its impact, an album that lingers long after it ends, like a half-remembered dream. For those willing to surrender to its hazy beauty, it offers not just songs, but a glimpse into the fragile, luminous world of an artist unafraid to leave things unresolved.